Denver Post Special Writer

Aardvark Records isn't really a record company -- not yet, anyway -- but it is the only disc-mastering studio in the Denver metro area. Disc-mastering, or disc-cutting, is the art of cutting grooves in records from tapes, and it has remained a somewhat mysterious process over the years -- even the most famous recording artists usually don't have any conception of what mastering entails. Paul and Kathy Brekus, the owners of Aardvark, are looking to change that.

A bit of background: Disk mastering is the first and most important step in manufacturing a record. The method transforms the music on a master tape into the grooves on an aluminum disc coated with lacquer. The tape is played through a disc-mastering console and converted by a lathe into the mechanical motion of a stylus. A sapphire needle (diamonds don't work as well) cuts the actual grooves into the disc -- called a lacquer in the trade -- which physically represent the music on the tape. It's the transition of music from an electric medium to mechanical.

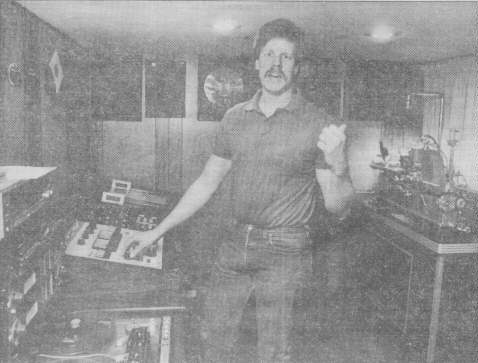

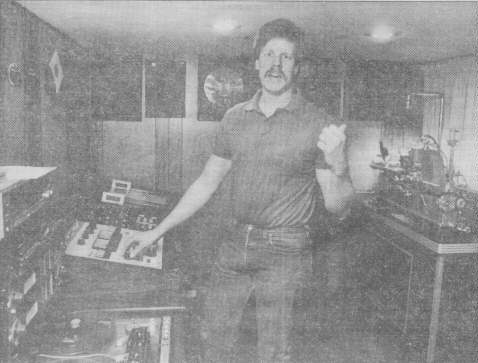

The mastering equipment is relatively cheap -- about half the price of equipping a 24-track recording studio. The major problem is that not many people know how to run it. Paul Brekus is one of those individuals fortunate enough to be doing exactly what he wants in life. He tore apart his first record player at 4 years old to find out how it made sound. "And as a teenager I experimented on how to cut records -- I even tried to inscribe records by blasting sound onto them from speakers," he laughed while exhibiting his basement studio recently. "I have just always wanted to be a mastering engineer."

Brekus eventually gained the use of a cheap record-cutting machine and learned his craft on it for 12 years. He courted his wife Kathy with the records he had made. Last January he bought a Scully disc-mastering machine from Hilltop Studios in Nashville, where everybody from Pat Boone to Dolly Parton has cut records. The lathe, designed in the 1930s, is fascinating -- the manufacturers made 800 castings, confident that they would sell out immediately. Today, there are still two of the lathes left at the factory, carrying a price tag of $72,000 apiece. Much of that expense is for the cutter head, comprised of two coils and no more ingeniously designed than the typical loudspeaker. The price doesn't reflect the accuracy of the piece, Brekus noted, but the secrecy with which it's made.

To begin the mastering process, Brekus puts a master tape on a tape machine and aligns it using meters and an oscilloscope. No adjustments made in the mastering room will magically improve a poorly engineered tape or a mediocre performance, Brekus can help somewhat with equalization and computerized pitch control. After calculating the proper speed, band width and record size for the length of music on the tape, he sets the lathe in motion on a lacquer. He engineers the bands between songs, the opening and outcue grooves and then checks the grooves and recording levels--looking through a microscope, Brekus can even "read" lacquers and tell what kind of music in on them by the pitch, depth and width of the grooves. (the best part is what happens to the groove thatís been cut--behind the lathe is a bottle filled with one long strand of lacquer that resembles a black fright wig.)

The reference lacquers are checked for variations in volume levels or tempos, excessive boominess or airiness in the bass frequencies or distortion in the treble range, or skips and buzzes at the beginnings of notes. If the lacquers are approved, the three other manufacturing steps continue--steps that the Brekusí farm out to Nashville-based companies they selected following personal tours.

Plating is a process that converts the master lacquers into stampers or molds that duplicate the grooves on the lacquers. Pressing occurs when the completed stampers mass-produce records on vinyl. Packaging completes the scenario, when the records are collated with album covers and dust sleeves.

The mastering process has been shrouded in secrecy by the industry--no one seems to want anyone else to know how they do it. Clients are usually permitted to see the equipment and the setup, but they have to leave the room during the actual process. Aardvark welcomes anyone to watch it do its stuff. Brekus will graduate from Metro State College next month with a 4.0 average in mathematics and computer science, and he knows heís easy pickings for a big corporation. But he refuses to don a suit and tie ever day to write another accounting program--he much prefers running his own business and dealing with the vagaries of the mastering trade. An example; Lacquers are made from nitrous cellulose, a cotton derivative--and when agriculturists used a different pesticide last year, they ruined the entire batch of lacquers for the recording industry.

With the advent of compact discs and cassettes, the Brekusí are aware that disc-cutting is a dying art, and they eventually want to pursue CD manufacturing. But records are still here for the moment, and they are quite pleased with their new business. Prior to Aardvark, the nearest disc-mastering facility for Denver area clients was in Cheyenne. (Plants in Nashville and Los Angeles are also popular sites). Now local artists can get first-rate product right here in town. Since opening four months ago, Aardvark has mastered records by Happy World, Horror Show, Billy & The Moonlighters, Runaway Express and the Cross-town Band. If you are interested, call 477-2273.